The TIF distress

Marathon County is tied with Washington County for having the most distressed TIFs | Wausonian decided to look closer

If you spend time reporting on Tax Increment Finance districts (otherwise known as TIF Districts or TIDs) you realize that everyone has an opinion on them and no two are generally the same.

First, what they are: TIF Districts are districts created to help ease blight. The point of them is to help provide incentives to developers to develop projects that otherwise they might not touch. Municipal leaders will tell you they’re one of the few tools available to help redevelop these troubled areas.

In fact, that’s exactly what they’re supposed to be used for. A project in a TIF District needs to pass the “but for” test; in other words “But for this money, the project would not happen.” Or put less in lawyer speak, without the money from TIF, no way the project would or could happen.

But what does that actually mean? Talk to ten people and you’ll get ten interpretations. You’ll see signs in empty tracts of land advertising that tax incentives are available. Shouldn’t that be exactly what developers want? Talk to them long enough, and you learn they love bare land. Already existing buildings are what they hate.

It can be more than an old, dilapidated building on the site. Environmental remediation can qualify. That cleanup can get expensive.

TIF is a mechanism that can pay for itself. (Kind of, as we will see later.) The idea is that you form this district, and the taxes from the value beyond that initial amount goes to the district to pay off its debt instead of the municipality, the school district, etc. The fancy new project brings up all the property values, increasing revenue from taxes, the district gets paid off, it closes, and kaboom: it’s a win-win-win, as Pete Weinschenck put it in a recent story.

What happens when that doesn’t work out? It’s not working out in six districts in Marathon County, according to the State Department of Revenue, which tracks districts.

What happens then? Districts can be extended. That gives more time to develop increment and pay off the debt.

But after that? Taxpayers will foot the bill. Are taxpayers in municipalities with the six distressed districts in danger of that?

This is a free story sent to all subscribers, but most stories like this go to paid subscribers exclusively. Considering joining the other Wausonians who have subscribed to support The Wausonian! And a big thanks to everyone who has subscribed so far - I’m humbled by your generous support. Hope you all had a great Fourth of July!

The worst TIF choice

Before we get to those six districts, I want to highlight one of the worst examples of TIF use I’ve ever seen. Stevens Point used TIF financing to help pay for the demolition and redevelopment of the CenterPoint MarketPlace. In its place, a technical college.

Now that we know how TIF districts work, can you see a problem with this already? Technical schools don’t pay taxes. And generating new property tax revenue is key to paying back a TIF. So having a non-profit as a very expensive centerpiece project seems… I don’t know, bad? You’re counting on all the other properties in the district, and any new projects, to cover the cost. Considering it cost almost $9 million when all said and done, well, that’s a tall order.

(That’s not a knock on the need Stevens Point had to redevelop its mall, or on Mid-State Technical College’s new campus. Just that it’s a very risky way to use TIF. Pairing it with a project that did generate increment like the Cobblestone Hotel that later built in the district would have been safer.)

And remember, that’s only new increment. In other words, if a property is worth $10 at the time a district opens, and it goes up to $11, you get the tax revenue from the $1.

Finance people at the time told me they thought it was crazy. They were right. Right now another district is helping fund the otherwise underwater (ie, losing money) district.

And that means THAT district can’t close. It means any gains those properties in that district are going to the TIF, and not to city coffers (or the school district, technical college, county, state, etc) to provide taxpayers some relief.

Are TIFs bad?

Like I said, that was the worst example. Most are either on the other end of the spectrum, or in the chasm between.

I once sat through a candidate forum where council and county board candidates were asked: “Are you in favor of TIF: Yes or no?” My jaw dropped as candidates struggled. Of course they did. It’s like saying “Sunlight, good or bad?” Sunlight is great, until you get too much of it. TIF is the same.

In fact, there is a limit to how much TIF a municipality is supposed to use. It’s based on property values. Only 12% is supposed to be locked in a TIF.

In Marathon County, there are several communities that are above this level. (Wausau is not one of them, by the way.)

Athens = 15.71%

Colby = 26.14%

Edgar = 13.1%

Hatley = 20.28%

Marathon = 22.15%

Stratford = 16.23%

Weston = 22.15%

Districts underwater

One might assume that districts that have too much TIF would also have districts that are underwater. But it turns out, only two from the over-the-limit list also have underwater districts. They are:

Athens 1

Date started: 9/25/1995

Supposed to close: 9/22/2022

Extended close: 9/25/2032

Edgar 3

Date started: 10/11/2004

Supposed to close: 10/11/2024

Extended date: 10/11/2034

Kronenwetter 1

Date started: 11/3/2004

Supposed to end: 11/3/2024

Extended date:11/3/2044

Kronenwetter 4

Date started: 11/3/2004

Supposed to end: 11/3/2024

Extended date: 11/3/2034

Maine 1

Date started: 9/29/1997

Supposed to end: 9/29/2020

Extended date: 9/29/2030

Schofield 3

Date started: 9/22/1997

Supposed to end: 9/22/2024

Extended to: 9/22/2034

Kronenwetter

Since Kronenwetter has two of them, let’s start with Kronenwetter. (The county Marathon is tied with, by the way, is Washington County. And five of its six distressed TIFs are in West Bend.)

I had a talk with the village’s community development director, Randy Fifrick. Fifrick told me when the village incorporated in 2002-2003, the main reason was so that the city could develop TIFs, since at the time towns couldn’t (I learned they can now, which was new to me).

The village created four TIFs with the idea they would spark economic development. There were some projects, and some like Woods Equipment Manufacturing Company and M&J Marine are doing well, but overall not nearly enough development has happened in TIF 1 and 4, which have been labeled distressed by the state. That qualifies them for an extension.

Neither of them right now are close to payback by that extended date.

What happened? They paid for expensive projects such as the Kowalski Road renovation (no relation to this author). And neither of them had an extensive enough project attached to them that would generate the increment back to pay back the borrowing on the TIF.

It’s a similar gamble to what Stevens Point did with its mall. Because the central project resulting from the TIF borrowing was a technical college that, by its nature, doesn’t pay taxes, they had to hope development pops up to cover it.

One thing different with Kronenwetter, however, is that at least Stevens Point had city owned land it could market to developers. Fifrick says the land inside the TIF is all privately owned. It really is a hope and a prayer. This is a dangerous way to do TIF.

Both districts have pretty stark debts compared to their fund balances: District one is in the hole $7,846,208.00; TIF 4 is a little better at $1,735,099. To be fair, TIF 4 has until 2044 to recover (TIFs always start out in the hole) and TIF 4 has until 2034. But neither as it stands are on track to break even.

Schofield’s TIF

Schofield’s distressed TIF, TIF No. 3, is so old it predates Clerk/Treasurer Lisa Quinn. Quinn told me that TIF 3 was, to the best of her knowledge, created to address water sewer issues on Grand Avenue.

The district will not close underwater, but that’s because TIF District No. 2 will serve as a donor district to help pay it back.

So easy peasy, right? Another TIF is helping out, the taxpayers don’t get a bill, and no one is the wiser. Right?

Folks such as former Wausau City Council member Dave Oberbeck disagree with that premise. There can be something of a notion that TIF is “free money” in the sense that its use doesn’t cost taxpayers anything.

But that’s not exactly true. When a district is created, the tax generation is essentially frozen at those levels, from someone looking outside of the TIF. Inside, the values are still growing, but the extra is going toward paying back the debt the district draws to work on projects inside that district.

An easy way to think about it (although nothing is terribly easy when it comes to TIF) is let’s say little Sally gets a $5 per week allowance from her dad. But Sally wants to buy something that costs $20. Dad says, “Ok, you can borrow the $20. Tell you what, I was going to raise your allowance to $6 per week. So I will keep giving you $5 per week, and the extra $1 will go toward paying back the debt.”

Sounds simple, right? Unfortunately, that’s the analogy as most people see TIF. But what is really happening is that Dad is freezing the allowance of Sally, Tim and little Bob to pay back Sally’s debts. Bob and Tim will start getting their full increased allowance once the debt is paid back, but until then they’re only getting their $5 too. But theoretically, the $6 only came about anyway because Sally wanted something in the first place.

This is the part that people miss. On your tax bill, a portion is going to the county, state, school district and technical school, besides your local municipality. When you create a TIF, those entities are no longer getting any increases in tax revenue from growth in the district. All because Sally wanted a new game.

To be fair, all those entities have a stake on the board of review that reviews TIFs. But these are rarely even contentious let alone actually halt a district’s creation or a move within a district. I haven’t seen it happen yet.

Overbeck warned his fellow city council members about this — while properties remain in a district, any new growth in value benefits the district, not the municipality, the county, the school district, etc. Over a five, 10 year period — OK, it’s a hardship, but it’s probably worth it for a good project.

But what does that look like for a district in the 90s? Especially one such as Schofield TIF District 3 — it snakes its way up Grand Avenue, one of the most commercial areas in Schofield. Imagine how much value was created from now until the 90s?

Athens

Athens Clerk/Treasurer Lisa Czech says that the Athen’s District 1 was created in 1995 when the village created its industrial park. The district fell behind because infrastructure ended up costing more than expected.

The district is currently in a deficit, but Czech says village leaders are hopeful the district will break even by the time it closes at the extended date of 2032.

Maine (or, Brokaw?)

There’s a very good reason Maine became a village, even if there was a little bit of backlash against the plan. Had it not, the village of Brokaw, nestled between the towns of Maine and Texas, would have dissolved. That would have saddled Maine and Texas with its debts, which was substantial.

So in taking on Brokaw into the new village, Maine took on its TIF District, which is distressed. It was started in 1997 as a way to develop the area west of the Wisconsin River, says Maine Administrator Keith Rusch. Rusch says the district will close in 2034 (the DOR says 2030) and will not be underwater when it closes.

District 1 is Maine’s only district, and the village has no intention to form any others.

Rusch says the combination of the mill closing (the whole reason Brokaw collapsed) and Brokaw overborrowing on the district, by much more than they should have been allowed, led to the financial troubles with the district.

Analyzing mill rate data is a little more challenging with Brokaw/Maine because of the unusual situation having a town become a village and absorbing another village. Rusch says Brokaw residents were paying $45 per $1,000 in total mill rate (including all the taxing entities) versus now when, as Maine residents, they’re paying $21 per $1,000. Maine’s taxes have decreased in the few years it has been a village.

Increasing amounts of TIF locked in districts

The Department of Revenue has a pretty cool tool for data visualization with TIF. It compares two charts: total mill rate for a municipality (including state, county, school, etc) overlaid with data from total equalized value and equalized value not in a TIF. In other words, as the two lines converge, you can see how much value is locked in TIF Districts over time.

The are more similarities between districts than there are differences. Two stark things really stand out.

The amount of value locked in TIF districts have been increasing lately. Almost universally. Especially in the last five years, municipalities have turned to TIF more and more.

There appears to be an inverse correlation between increasing equalized value and tax rates. As value increases, mill rates decrease, and vice versa.

Although it’s outside our coverage area, Stevens Point presents an interesting example. Stevens Point’s mill rates were falling as its equalized values rose in recent years, but that changed around 2017: in ‘18 and ‘19, the amount of value locked in TIFs dramatically rose. It went from $106 million locked in TIF in 2017 to $230 million locked up in 2019. As that changed, mill rates rose instead of fell, a strange anomaly as equalized value still rose.

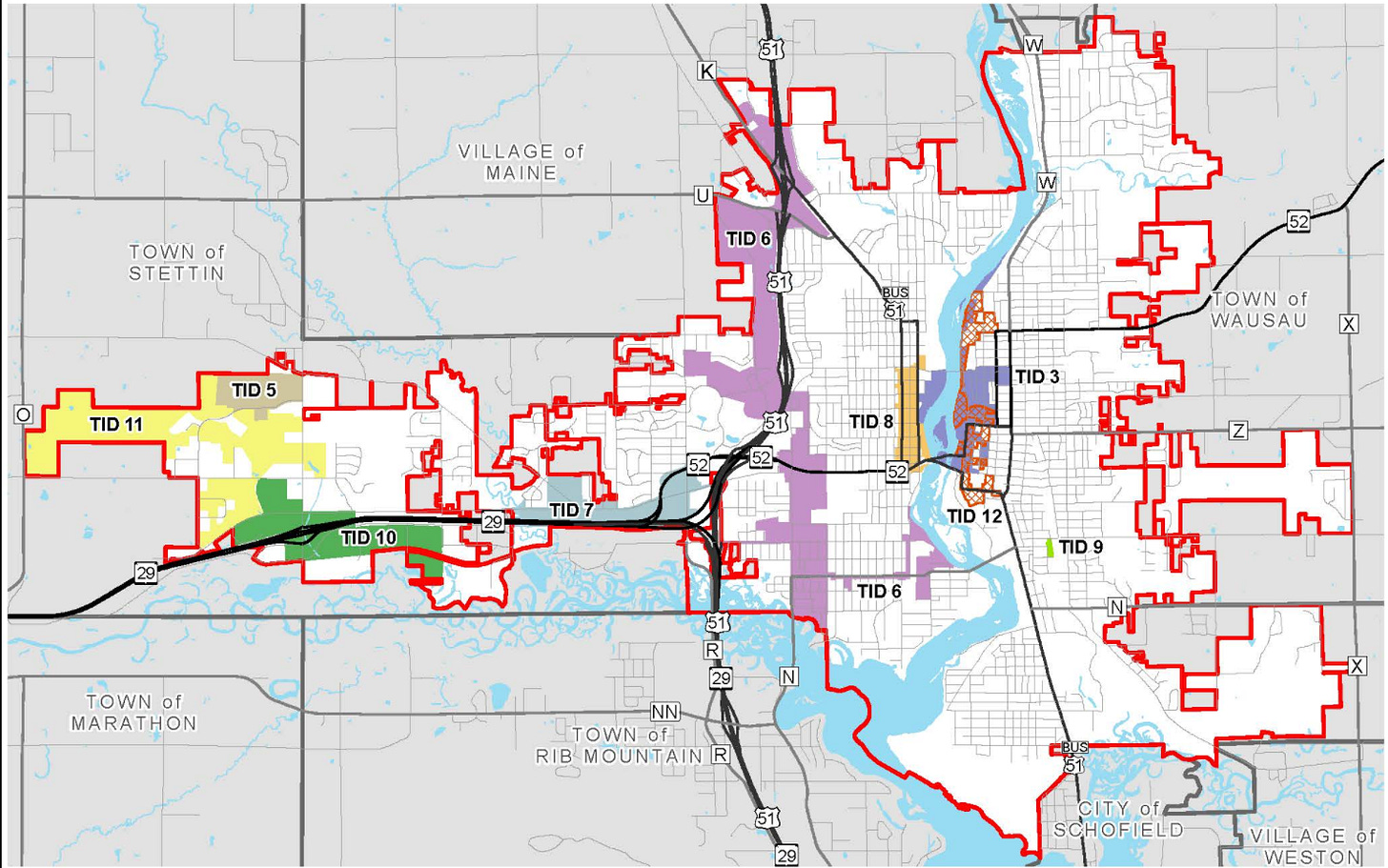

That’s not the case with Wausau. Wausau’s mill rates have fallen almost perfectly with the rise of equalized value, and vice versa. It’s almost a perfect correlation. Wausau’s also look different than Point in that Point had years in the mid-2000s where it had almost no value locked in TIFs; Wausau’s have been steadily growing. Wausau went from $256 million locked in TIF in 2017 to $359 million. It seems like a big jump and it is, but looking more long-term it’s a more steady rise.

How about for Kronenwetter? Much more boring. The amount locked in TIF stayed pretty steady over the years since around 2010, and mill rates have dropped as value has risen.

Schofield’s is also a pretty similar story, with mill rates dropping as value increases. Schofield is more similar to Stevens Point and Wausau in that the amount locked in TIF has changed quite a bit. TIF-locked $21.7 million in 2017 grew to $31 million in 2019.

Do TIF Districts lower taxes?

Analyzing total mill rate data (including all taxes) for changes over time yields some interesting results. In almost all cases, mill rates changes are inversely correlated with equalized property values. In other words, as values increase, mill rates go down.

How can we apply TIF districts to this equation? The DOR’s data visualization tool gives us some insight. It shows us equalized values, with and without TIF districts included. We can see the change in district usage over time.

One thing that becomes clear looking at this data. The amount of TIF being used over time generally increases, and rarely decreases.

We can look at Wausau’s for an example. Wausau had $200 million in TIF in 2010, according to the DOR’s data visualization tool; that increased to $344 million in 2020. Schofield had $19 million in 2010; in 2020 it had $30 million. Stevens Point exploded in TIF; it went from $34 million in 2010 to $272 million in TIF.

An oddity is Rothschild: it’s TIF nearly completely disappeared in 2010, implying it closed all of its districts by that year. (It had $84 million in TIF in 2009). By 2020 it had added some TIF value again: about $14 million worth.

Lessons learned

None of the distressed districts are quite as reckless as Stevens Point’s downtown mall project TIF, but it’s interesting that most of the distressed TIF districts in the county were the result of general TIFs, versus those created for a very specific project.

The most successful districts seem to at least center on one specific project, though others might be added to the district of course. Wausau’s River District is a good example — it will fund a series of developments along the Wisconsin River, bringing housing, commercial and retail to an area that had been an industrial wasteland.

Debates will continue about TIF Districts — some use them without a thought, others take a hard line against ever using them, and plenty others are somewhere in between those two extremes. TIF is like any tool — there are probably more than one right way to use it, but also plenty of wrong.

But at the risk of stretching the analogy too far, it’s important to put your tools away. TIF can be a great tool to spark projects, but the gains come when you close them, so the municipality, along with the county, state, school district, etc can actually get the new tax revenue generated by the TIF in the first place.

Thank you for reading this long feature of The Wausonian. Most pieces like this are for subscribers only. To see the archive, get stories like this in the future, and be able to leave comments, consider becoming a paid subscriber and supporting local journalism. And thanks to all of our subscribers so far!